by Steve C. Halbrook

In Christian circles, much of the immigration debate centers on what the appropriate Christian response should be according to Scripture. Opinions vary when it comes to immigration restrictions and border security. We have previously given our own perspective here.

What about perspectives in Christian history? It is always good to examine history and see how our own views measure up to the past, and determine whether the past includes any biblical wisdom. History is not infallible—but it can be helpful in exposing our own blind spots.

One particular era that should never be overlooked in history is that of the American Pilgrims and Puritans. Both groups are heirs to the Protestant Reformation and held to some of the best theology that has been discovered in Christian history.

Despite a series of trials and hardships, the Pilgrims—with nothing short of inspirational faith—successfully established Plymouth Colony, America's second permanent English settlement, in order to worship God in peace according to their understanding of Scripture. The American Puritans, men of faith who would also settle in the New England area, likewise sought religious liberty—and to establish "A City on a Hill" which would stand out as a church and society that worshiped and lived according to God's word.

Naturally, these great men of faith would experience the challenge of deciding where to draw the line when it comes to admitting others into their land. And admission was something that they took very seriously: for to live among the Pilgrims and Puritans, one was at least required to be peaceful, to hold to the fundamentals of Christianity, and to be willing to assimilate. Preservation of the Christian social order was a high priority. As one author comments on the immigration policy of the Massachusetts Bay Puritans:

In short, the Pilgrims and Puritans were cautious because of the threat of those—which they experienced firsthand—who would undermine the Christian social order by misguided ideas, criminal behavior, godless lifestyles, and heretical teachings. As such, it was the duty of magistrates, as public servants, to enforce a controlled immigration policy. To fail to do so could lead to anarchy and the tyrannical rule of God's enemies.It seems a fair inference, from the writings of the founders of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and from a careful study of their early government, that it was their aim to found a state based on the Scriptures, interpreted strictly according to their own ideas. Accordingly, it seemed wise and even essential that all persons differing in matters of faith and worship should be prohibited from settling amongst them.[1]

No doubt the Pilgrims and Puritans understood the teaching that "A little leaven leavens the whole lump" (Galatians 5:9); and perhaps they believed that by controlling immigration in the way that they did, rulers were applying their mandate to help Christians to "lead a peaceful and quiet life, godly and dignified in every way" (1 Timothy 2:2b).

Were the controlled immigration laws of the Pilgrims and Puritans contrary to evangelism? It doesn't appear that they thought so. When the Puritan colonies of Massachusetts and Connecticut and the Pilgrim colony of Plymouth created Articles of Confederation for mutual defense against hostile Indians in 1672, they affirm in the preamble that they "all came into these parts of America with one and the same end and aim viz. to advance the kingdom of our Lord Jesus Christ."[2]

This was all said while their immigration laws were in place—and while the Articles itself required immigration control (as we discuss in this article). And we must also note that if a society strongly restricts whom it allows in, it doesn't mean that that society cannot send people out to evangelize those outside of its borders. Perhaps, too, it can be said that when a society protects itself from outsiders who would infect it, bad leaven that could negatively affect the theology of its missionaries can be minimized—to the benefit of outsiders whom they would evangelize.

The following includes information on Pilgrim and Puritan immigration laws, as well as commentary by some of their leaders. Whether or not their approach was right in every respect, it is worth considering to the extent that it conforms to biblical principles, as it can inform a nation how it should frame its immigration laws. Even in the case of America, which is far from being a Christian nation, there may be principles for informing our current immigration policy—as well as applications to strive for should we become a Christian nation again.

The Immigration Policy of the Pilgrims

Admission Left to the Discretion of Magistrates

The Pilgrims of Plymouth Colony held that civil magistrates should have discretionary power to determine whether a stranger could dwell among them. In 1637 the famous Puritan John Winthrop affirms this while defending the same policy in Puritan Boston. In a critique of a one Henry Vane, he writes:

And if he had inquired of our neighbors at Plymouth, they could have told him that their practice hath been upon the like law, for many years, I mean in referring it to the discretion of the magistrates to receive and reject such as come to them.[3]In 1636 in Plymouth Colony, it was decreed

That no person or persons hereafter shall be admitted to live and inhabit within the Government of New Plymouth without the leave and liking of the Governor or two of the Assistants at least.[4]

This was reinforced in a law passed in 1658 that recognized the need to prohibit the admission of those who would disturb the social order:

Whereas it hath been an ancient and wholesome order bearing date March the seventh 1636 that no person coming from other parts be allowed an inhabitant of this jurisdiction but by the approbation of the governor and two of the magistrates at least and that many persons contrary to this order of court are crept into some townships of this jurisdiction which are and may be a great disturbance of our more peaceable proceedings, be it enacted by the court and the authority thereof that if any such person or persons shall be found that hath not doth not or will not apply and approve themselves so as to procure the approbation of the governor and two of the assistants that such be inquired after, and if any such persons shall be found that either they depart the government or else that the court take some such course therein as shall be thought meet.[5]

In the year 1636 Plymouth Colony, and a year later Massachusetts Bay, enacted laws to the effect that no town or person should receive any stranger with intent to entertain such person more than three weeks without the consent of the authorities. The purpose of these laws, it is said, was to prevent the coming of individuals who might further political strife or become an economic burden. Then, as now, the fear of foreign radicals and paupers was abroad in the land ...[6]

On Refusing to Admit Roger Williams

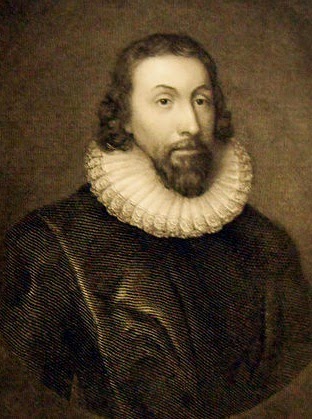

|

| While refusing Roger Williams entry into Plymouth, Governor Edward Winslow (above) welcomed him as a neighbor to the colony and provided his household with monetary assistance. |

Roger Williams (1603-1683) was considered by William Bradford of Plymouth Colony as "godly and zealous"—but Bradford also had some serious disagreements with him. Williams, of course, is famous with religious pluralists for his views on toleration. However, Williams had an extreme view of toleration which—along with other opinions (whether right or wrong)—made it difficult for him to co-exist with many other Christians in New England.

For example, one reason that Williams was banished from Salem was for holding that "the magistrate ought not to punish the breach of the first

table [commandments 1-4 of the Ten Commandments], otherwise than in such cases as did disturb the civil peace."[7]

After leaving Salem, Williams attempted to settle in an area that turned out to be part of Plymouth Colony. Plymouth refused him admission (it may or may not have had to do with his history with the colony, as Williams once resided there), but welcomed him to live close to the settlement as a neighbor. A couple years later, in a letter to Governor John Winthrop of the Puritan Massachusetts Bay Colony, Governor William Bradford of Plymouth Colony recounts Plymouth's discretion in dealing with Roger Williams:

There was not long since here with us Mr. Cottington & some other of your people, who brought Mr. Williams with them and pressed us hard for a place at, or near Sowames, the which we denied them; then Mr. Williams Informed them of a spacious land called Monachunte, touching which the solicited our good will, to which we yielded, (so they would compound with Ossamequine) the which we heard was ill taken by you, but you may please to understand that it is not in our patent (though we told them not so) for it only was excepted out of it.) And we thought (if they liked it) it were better to have them, (though they differ in opinions) then (happily) worse neighbors, both for us, & you. We think it is also better for us both to have some strength in that Bay.[8]When Williams was refused admission (this was in 1636), William Bradford was not Plymouth's governor, but Edward Winslow (1595-1655). In his own words, Roger Williams describes the situation as follows:

I pitched, and begun to build and plant at Seekouk, now Rehoboth, but I received a letter from my ancient friend, Mr. Winslow, then Governor of Plymouth, professing his and others' love and respect to me; yet lovingly advised me, since I was fallen into the edge of their bounds, and they were loath to displease the Bay, to remove but to the other side of the water, and there, he said, I had the country free before me, and might be as free as themselves, and we should he loving neighbors together.[9]

[T]hat great and pious soul, Mr. Winslow, melted and kindly visited me at Providence, and put a piece of gold into the hands of my wife, for our supply.[10]

On Welcoming the godly, and the Dangers of Welcoming the Profane

Robert Cushman (1577-1625) was a friend of Bradford who helped to organize the Mayflower voyage and was an agent for Plymouth Colony in London. Cushman stated that the colony would "right heartily welcome" those who were "honest, godly and industrious men."[11] However, he warned about the consequences of admitting the ungodly:

[F]or other of dissolute and profane life, their rooms are better than their companies; for if here where the Gospel hath been so long and plentiful taught, they are yet frequent in such vices as the heathen would shame to speak of, what will they be when there is less restraint in word and deed?[12]One author summarizes the Pilgrims' immigration policy as such:

They heartily welcomed to their little State all men of other sects, or of no sects, who adhered to the essentials of Christianity and were ready to conform to the local laws and customs.

Naturally they did not welcome zealots who came for the avowed purpose of overthrowing their Church, and when such intruders became troublesome they did not hesitate to drive them out.[13]

William Bradford on the Influx of Wicked Inhabitants

|

| William Bradford's concerns about how Plymouth Colony quickly became infected by the wicked imply the importance of a controlled immigration policy. |

In Of Plymouth Plantation, Bradford describes a serious problem at Plymouth: the colony had quickly become infected by a large number of wicked people. In relating how this came about, he discusses:

- the reality of the tares among the good seed

- how the colonists, in their desire for help in establishing the colony, admitted those who would prove to be untoward

- that some, for the sake of profit, would transport ungodly people to the colony

- that even the ungodly may be willing to dwell with the people of God in order to receive the blessings that accompanies them

But it may be demanded how came it to pass, that so many wicked persons, and profane people, should so quickly come over into this land, and mix themselves amongst them? Seeing it was religious men that began the work, and they came for religion's sake? I confess this may be marveled at, at least in time to come, when the reasons thereof should not be known; and the more because here was so many hardships, and wants met withal. I shall therefore endeavor to give some answer hereunto.

1. And first, according to that in the gospel, it is ever to be remembered, that where the Lord begins to sow good seed, there the envious man will endeavour to sow tares.

2. Men being to come over into a wilderness, in which much labor and service was to be done about building and planting, etc., such as wanted help in that respect, when they could not have such as they would, were glad to take such as they could; and so many untoward servants, sundry of them proved, that were thus brought over, both men, and women kind; who when their times were expired, became families of themselves, which gave increase hereunto.

3. Another, and a main reason hereof, was: that men finding so many godly disposed persons willing to come into these parts; some began to make a trade of it, to transport passengers and their goods; and hired ships for that end; and then to make up their freight, and advance their profit, cared not who the persons were so they had money to pay them. And by this means the country became pestered with many unworthy persons, who being come over, crept into one place or other.

4. Again, the Lord's blessing usually following His people, as well in outward, as spiritual things (though afflictions be mixed withal) do make many to adhere to the People of God, as many followed Christ for the loaves' sake, John 6:26, and a mixed multitude came into the wilderness, with the People of God out of Egypt of old, Exodus 12.38. So also there were sent by their friends, some under hope that they would be made better; others that they might be eased of such burdens, and they kept from shame at home, that would necessarily follow their dissolute courses. And thus by one means or other, in 20 years' time, it is a question whether the greater part be not grown the worser?[14]

The Immigration Policy of the Puritans

The Massachusetts Body of Liberties

The Massachusetts Body of Liberties, adopted in 1641 by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts Bay, was New England's first code of laws[15]—and effectively America's first constitution. It was compiled by the Puritan Nathaniel Ward (1578-1652) and promulgated in 1641. The following observation has been made about this legal code:

Perhaps no other writing from the Puritan Era had so far-reaching an effect as this document, which laid the foundations of Massachusetts liberties, for which New Englishmen fought against the Empire in the 1680's and during the American Revolution, and which became a pattern of the United States Constitution. It is remarkable as a code of law, in that it lays out a structure of jurisprudence in terms of liberties rather than restrictions. In this it echoes the Magna Charta, and foreshadows our Bill of Rights. Drawing upon the Magna Charta and English Common Law, it was largely the work of one man, the remarkable Puritan thinker and writer, Nathaniel Ward.[16]

The Massachusetts Body of Liberties includes a section titled "Liberties of Foreigners and Strangers." Here the code provides for the admission of two classes of people: Christians in need, and those who have suffered shipwreck:

89. If any people of other Nations professing the true Christian Religion shall flee to us from the Tyranny or oppression of their persecutors, or from famine, wars, or the like necessary and compulsorily cause, They shall be entertained and succored among us, according to that power and prudence, God shall give us.

90. If any ships or other vessels, be it friend or enemy, shall suffer shipwreck upon our Coast, there shall be no violence or wrong offered to their persons or goods. But their persons shall be harbored, and relieved, and their goods preserved in safety till Authority may be certified thereof, and shall take further order therein.[17]

The Book of the General Laws and Liberties Concerning the Inhabitants of the

In its section on Strangers, The Book of the General Laws and Liberties Concerning the

Inhabitants of the Massachusetts, published in 1648, forbids allowing a stranger admission without the allowance of the magistrate. Fines were to be imposed for violating this law:

It is ordered by this Court and the Authority thereof; that no town or person shall receive any stranger resorting hither with intent to reside in this Jurisdiction, nor shall allow any lot or habitation to any, or entertain any such above three weeks, except such person shall have allowance under the hand of some one Magistrate, upon pain of every town that shall give, or sell any lot or habitation to any not so licensed such fine to the country as that county court shall impose, not exceeding fifty pounds, nor less then ten pounds. And of every person receiving any such for longer time then is here expressed or allowed, in some special cases as before, or in case of entertainment of friends resorting from other parts of this Country in amity with us, shall forfeit as aforesaid, not exceeding twenty pounds, nor less then four pounds: and for every month after so offending, shall forfeit as aforesaid not exceeding ten pounds, nor less then forty shillings. Also, that all Constables shall inform the Courts of newcomers which they know to be admitted without licence, from time to time. [18]

The Quakers

|

| To protect the community from the dangerous teachings of the Quakers, New England enacted penalties which to a certain extent deterred their immigration. |

With the exception of Rhode Island, the New England colonies set out to protect themselves from the dangerous teachings of the Quakers with penalties that to a certain extent deterred their immigration. According to Proper,

For a period of several years, beginning with 1656, the records of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and indeed of all of the New England Colonies, except Rhode Island, are filled with legislation designed to prevent the coming of the Quakers and the spread of their "accursed tenets." Whippings, imprisonment, banishment, and in a few instances capital punishment, were the order of the day. To what extent these various laws restricted the immigration of this sect, it is, of course, impossible to ascertain. That they were not prohibitive, and consequently did not meet the expectations of the authorities, is painfully evident; for, in spite of the severe penalties, members of that sect continued to come ... There can be but little doubt, however, that many Quakers were deterred from immigrating to these inhospitable shores; while, judging from the throngs that afterward poured into Pennsylvania and the Jerseys, it is fair to presume that, had they received a welcome to the New England Colonies ... a very considerable number would have found homes in that section.[19]During King Philip's War (1675-1678), where Indians waged war with Pilgrims, Puritans, and their Indian allies, a "Puritan Explanation" was passed in 1675 where

the Massachusetts General Court identified the sins of the colony, called for a general humiliation and repentance before God, and established measures calculated to begin the work of reformation and to meet the challenge of King Philip and his warriors.[20]The measures for reformation include the following prohibition against admitting Quakers:

And touching the law of importation of Quakers, that it may be more strictly executed, and none transgressing to escape punishment,—It is hereby ordered, that the penalty to that law averred be in no case abated to less than twenty pounds.[21]

Catholics and Jesuits

Given the dangerous theological and political views of Roman Catholics, the Puritans would naturally be uneasy about admitting them into the colonies. There was especially concern about the Jesuits (Catholics who promoted the Counter-Reformation), who had influence over the Indians. In Colonial Immigration Laws, Emberson Edward Proper writes:

The charter of the Massachusetts Bay Company contained no direct or implied reference to Catholics, and nearly a quarter of a century passed before laws aimed at their exclusion were passed; though it is very probable that none of that persuasion were permitted to live in either of the Massachusetts Colonies. The order giving magistrates full authority over the admission of immigrants, could easily be made to exclude all persons professing obedience to the Church of Rome. The French Catholics had made settlements in the valley of the St. Lawrence and on the shores of Nova Scotia long before the establishment of permanent colonies in New England; and ten years before the landing of the Pilgrims, the Jesuits had made their way to the French settlements. From that time until the American Revolution, this strange sect, largely because of their influence over the Indians, became the terror of the frontier settlers, and their presence in any of the colonies was an occasion for alarm and distrust.[22]The Massachusetts Colony took strong measures to prevent Jesuits and Catholic ecclesiastical persons from entering the land. In 1647 the following act was passed:

An Act Relating to Jesuits.

This court taking into consideration the great wars, combustions and divisions, which are this day in Europe, and that the same are observed to be raised and fomented chiefly by the secret underminings and solicitations of those of the Jesuitical order, men brought up and devoted to the religion and court of Rome, which hath occasioned divers states to expel them their territories, for prevention whereof among ourselves:

It is ordered and enacted by authority of this court, that no Jesuit, or spiritual or ecclesiastical person (as they are termed) ordained by the authority of the pope or see of Rome, shall henceforth at any time repair to, or come within this jurisdiction: and if any person shall give just cause of suspicion, that he is one of such society or order, he shall be brought before some of the magistrates, and if he cannot free himself of such suspicion, he shall be committed to prison, or bound over to the next court of assistants, to be tried and proceeded with, by banishment or otherwise as the court shall see cause.

And if any person so banished, be taken the second time within this jurisdiction, upon lawful trial and conviction, he shall be put to death. Provided this law shall not extend to any such Jesuit, spiritual or ecclesiastical person, as shall be cast upon our shores by shipwreck or other accident, so as he continue no longer than till he may have opportunity of passage for his departure; nor to any such as shall come in company with any messenger hither upon public occasions, or merchant, or master of any ship belonging to any place, not in enmity with the state of England, or ourselves, so as they depart again with the same messenger, master or merchant, and behave themselves inoffensively during their abode here.[23]

Nothing further is found on this subject until the year 1700, when the Court again declared that the Jesuits and Popish Priests had "by subtile insinuations seduced and withdrawn the Indians from obedience, and stirred them up to sedition and open rebellion."[24] To prevent this threatened calamity, all such persons then within the jurisdiction should immediately depart or surfer "perpetual punishment."

In a letter published among the Hutchinson Papers, a writer of that period declares, "The aim of the Jesuits is to engage the Indians to subdue New England."[25] The wonderful influence which they exerted over the Indians, and the fear that they would incite the savages to massacre the English settlers seems to have been the chief motive in all the colonies for the severe laws which were passed against that Order. Whether these laws likewise served to restrict the immigration of Catholic laymen can only be conjectured. It is certain that no appreciable number of that sect were to be found in Massachusetts prior to the Revolution. They could not become citizens or voters, being unable to take the necessary oath of allegiance; and in various other ways the Massachusetts Colony manifested her unwillingness to receive settlers of that persuasion.[26]

|

| The Articles of Confederation of 1672 united the Puritan and Pilgrim colonies against hostile Indians. Article 13 recognizes the discretionary right of towns to determine who could be admitted. |

In 1672, the Puritan colonies of Massachusetts and Connecticut and the Pilgrim colony of Plymouth confederated for mutual defense against hostile Indians. The preamble to the Articles of Confederation reads:

Whereas we all came into these parts of America with one and the same end and aim viz. to advance the kingdom of our Lord Jesus Christ; and to enjoy the liberties of the Gospel in purity with peace; and whereas in our settling by a wise providence of God we are further dispersed upon the sea coasts and rivers than was first intended; so that we cannot according to our desire with conveniency communicate in one government and jurisdiction; and whereas we are compassed with people of several nations and strange languages; which hereafter may prove injurious to us and our posterity and forasmuch as the natives have formerly committed sundry insolencies and outrages upon several plantations of the English; and have several times combined themselves against us; and seeing by reason of our distance from England (our dear native country) we are hindered both from that humble way of seeking advice and reaping those comfortable fruits of protection which we might otherwise well expect; we therefore account it our duty as well as safety to enter into a confederation for mutual help and succor in all our future concernments; that as in nation and religion; so in other respects; we be and continue one; according to the tenure and true meaning of the ensuing articles ...[27]

13. It is also agreed for settling of vagabonds and wandering persons removing from one colony to another to the dissatisfaction and burden of the places where they come as daily experience showeth us; for the future it is ordered, that where any person or persons shall be found in any jurisdiction to have had their abode for more then three months and not warned out by the authority of the place; and in case of the neglect of any person so warned as abovesaid to depart; if he be not by the first opportunity that the season will permit sent away from constable to constable; to the end that he may be returned to the place of his former abode; every such person or persons shall be accounted an inhabitant where they are so found, and by them governed and provided for as their condition may require and in all such cases the charge of the constables to be borne by the treasurer where the said constables doe dwell ... [29]

The following is a sampling of immigration laws enacted in Puritan New England as covered in Josiah Henry Benton's Warning Out In New England. For a more thorough treatment, read the book online here.

Boston, MA (June 13, 1659):

Whereas sundry inhabitants in this town have not so well attended to former orders made for the securing the town from charge by sojourners, inmates, hired servants, journeymen, or other persons that come for help in physick [medical treatment?] or chyrurgery [surgery?], whereby no little damage hath already, and much more may accrue to the town. For the prevention whereof it is therefore ordered, that whosoever of our inhabitants shall henceforth receive any such persons before named into their houses or employments without liberty granted from the select men, shall pay twenty shillings for the first week, and so from week to week, twenty shillings, so long as they retain them, and shall bear all the charge that may accrue to the town by every such sojourner, journeyman, hired servt., inmate, &c., received or employed as aforesaid. Provided, always, that if any person so receiving any shall, within fifteen days, give sufficient security unto the select men that the town may be secured from all charges that may arise by any person received, and that the persons so received be not of notorious evil life and manners, their fine abovesaid shall be remitted or abated according to the discretion of the select men. And it is further ordered that if after bond given by any, they give such orderly notice to the select men that the town may be fully cleared of such person or persons so received according to law, then their bonds shall be given in again.[30]

In 1648 a stranger was admitted an inhabitant of Woburn and permitted to buy land for his convenience, "provided he unsettle not any inhabitant and bring testimony of his peaceable behaviour which is not in the least measure questioned."[31]Lancaster, MA:

[F]or the better preserving of the purity [of] religion and ourselves from the infection of error [we are] not to distribute allotments and to receive into the plantation as inhabitants any excommunicate or otherwise profane and scandalous (known so to be) nor any notoriously erring against the doctrine and discipline of the churches and the state and government of this Common weale.[32]

We shall all of us in the said town faithfully endeavor that only such be received to our society & township as we may have sufficient satisfaction in, that they are honest, peaceable, & free from scandal and erroneous opinions.[33]

In 1670 a person was appointed and instructed "to go from house to house about the town, once a month, to inquire what strangers are come, or have privily thrust themselves into town and to give notice to the Selectmen in being, from time to time, and he shall have the fines for his pains or such reasonable satisfaction as is meet."[34]Massachusetts Bay, MA (1650):

Whereas we are credibly informed that great mischiefs and outrages have been wrought in other plantations in America by commanders, and soldiers of several qualities, and other strangers issuing out of other parts, usurping power of government over them, plundering of their estates, taking up arms, and making great divisions amongst the inhabitants where they have come, to prevent the like mischief in this jurisdiction, this court doth order, and it is hereby enacted, that henceforward all strangers, of what quality soever, above the age of sixteen years, arriving here in any ports or parts of this jurisdiction in any ship or vessel, shall immediately be brought before the governor, deputy governor, or two other magistrates, by the master or mate of the said ships or vessels, upon the penalty of twenty pounds; for default thereof, there to give an account of their occasions and business in this country, whereby satisfaction may-be given to this commonwealth, and order taken with such strangers as the said governor, deputy governor, two assistants, or the next county court shall see meet; and that the law for entertaining of strangers be strictly put in execution, and this order to be posted up upon the several meetinghouses doors, or posts, or other public places in the port towns of this jurisdiction. And it is ordered, that the captain of the castle shall make known this order to every ship or vessel as it passeth by, and the constables of every port town shall endeavor to do the like to such ships or vessels before they land their passengers; and that a true record be kept of all the names of such strangers, and their qualities, by the clerks of the writs, who shall have the names given them by the said governor or magistrates, to be returned to the next immediate sessions of the General Court. This to continue and be in force till the next session.[35]

It is said that this order, although general in its terms, was passed specially with reference to the fact that it was known that many of the friends of Wheelwright and persons who entertained the Antinomian heresy were about to arrive upon a ship from England.

But in October, 1651, another order, continuing it in force without limit of time, was made … [36]

Thomas Shepard on Allowing Subversives into the Land

|

| For Thomas Shepard, controlled immigration was necessary to protect the commonwealth from those who would subvert the laws and persecute Christians. |

Shepard strongly advocated a controlled immigration policy in order to protect Massachusetts from those who would subvert the laws and persecute Christians. This is seen during a controversy where it was feared that a number of inhabitants who displayed contempt for the town's laws and ministers could take over the town with the arrival of like-minded individuals said to be on their way. Accordingly, Shepard issued the following warning while preaching to the General Court:[37]

1. If you would have the walls of magistracy be broken down, (the means to preserve the church and means among you,) if they make laws, deride them; if they execute laws, appeal from them.

2. Would you have confusion, the mother of discord, among the people? let every man once, one day in the year, turn magistrate, and outface authority, and profess it is his liberty. Would you have rapines, thefts, injustice abound? let no man know his own, by removing the landmark, and destroying properties.

3. Would you have God's ordinances in the purity of them removed? keep out the load of superstition, but yet, for peace sake, suffer a few seeds to be sown among you.

4. Would you have all the messengers of the gospel at first reviled, at last massacred? profess they are no better than scribes and Pharisees, persecuting Egyptians, enemies to the Lord Jesus, and the more devout the worse ...

5. Would you ruin the gospel? set not Popery against it, but gospel against gospel, promises against promises, Christ against Christ, Spirit against Spirit, grace against grace, and then he is twice beaten that falls by his own weapons.

6. Would you have oppressors set over you, to remove ordinances, to increase your burdens? maintain this principle then, that they will not assault us first by craft and subtlety, but openly and violently.

7. Would you have this state in time to degenerate into tyranny? take no care, then, for making laws. When they are made, would you have all authority turned to a mere vanity? be gentle, and open the door to all comers that may cut our throats in time; and, if being come, they do offend, threaten them and fine them, but use no sword against them. You fathers of the country, be not offended; this I speak not to disparage any; the practice speaks otherwise; I only forewarn; I hope the Lord has prepared better days and mercies for us; I am sure he will, if what means we have we preserve, and what we preserve, we, through grace, shall improve.[38]

This appeal for immigration control may have, according to Michael P. Winship, "helped prompt the Court that May to pass a law forbidding any town to take in strangers for more than three weeks without the permission of the magistrates."[39]

John Winthrop's Defense of Controlled Immigration

|

| "If we here be a corporation established by free consent, if the place of our cohabitation be our own, then no man hath right to come unto us etc. without our consent." -- John Winthrop |

A time of trouble known as the Antinomian Controversy prompted Winthrop to advocate controlled immigration to prevent subversives from undermining the Christian social order. This is seen in his "Declaration in Defense of an Order of the Court." Some background:

The Massachusetts General Court, as an aftermath of the proceedings against Wheelwright in March, 1636/37, passed an order at the May session "to keep out all such persons as might be dangerous to the commonwealth, by imposing a penalty upon all such as should retain any, etc., above three weeks, which should not be allowed by some of the magistrates; for it was very probable, that they [the Antinomians] expected many of their opinion to come out of England from Mr. Brierly his church, etc." Journal, 1. 219. The protests of those against whom the order was really directed were so strenuous that this defense of the Court's action was drawn up.[40]

In his Declaration, Winthrop argues that

- Admission to a commonwealth requires the consent of the people and the civil magistrates.

- Those deemed as harmful to society may be lawfully rejected admission.

- If churches can lawfully receive or reject individuals, then so can a commonwealth.

- If a family can exercise discretion in whom it entertains, then so can a commonwealth.

- Admitting someone out of mercy requires such a person to first be in misery; and a commonwealth is not bound to be merciful to its own ruin.

- It is better to deny one admittance than to admit him and then expel him.

- If John 2:10 forbids receiving those who don't bring the true doctrine into one's house, then by that same reason such persons should not be received by a commonwealth.

- If anyone is turned away who shouldn't have been, the problem is not with the law, but with the one enforcing the law.

- The intent of the law requiring admission via the discretion of magistrates is to preserve the welfare of the commonwealth.

- Rejecting admission to even certain Christians is not akin to rejecting Christ, for some Christians hold views that endanger the commonwealth.

A DECLARATION IN DEFENSE OF AN ORDER OF COURT

MADE IN MAY, 1637

by John Winthrop

A Declaration of the Intent and Equity of the Order made at the last Court, to this effect, that none should be received to inhabit within this Jurisdiction but such as should be allowed by some of the Magistrates

For clearing of such scruples as have arisen about this order, it is to be considered, first, what is the essential form of a common weale or body politic such as this is, which I conceive to be this—The consent of a certain company of people, to cohabit together, under one government for their mutual safety and welfare.

In this description all these things do concur to the well being of such a body, 1 Persons, 2 Place, 3 Consent, 4 Government or Order, 5 Welfare.

It is clearly agreed, by all, that the care of safety and welfare was the original cause or occasion of common weales and of many families subjecting themselves to rulers and laws; for no man hath lawful power over another, but by birth or consent, so likewise, by the law of propriety, no man can have just interest in that which belongeth to another, without his consent.

From the premises will arise these conclusions.

1. No common weale can be founded but by free consent.

2. The persons so incorporating have a public and relative interest each in other, and in the place of their co-habitation and goods, and laws etc. and in all the means of their welfare so as none other can claim privilege with them but by free consent.

3. The nature of such an incorporation ties every member thereof to seek out and entertain all means that may conduce to the welfare of the body, and to keep off whatsoever doth appear to tend to their damage.

4. The welfare of the whole is to be put to apparent hazard for the advantage of any particular members.

From these conclusions I thus reason.

1. If we here be a corporation established by free consent, if the place of our cohabitation be our own, then no man hath right to come into us etc. without our consent.

2. If no man hath right to our lands, our government privileges etc., but by our consent, then it is reason we should take notice of before we confer any such upon them.

3. If we are bound to keep off whatsoever appears to tend to our ruin or damage, then we may lawfully refuse to receive such whose dispositions suit not with ours and whose society (we know) will be hurtful to us, and therefore it is lawful to take knowledge of all men before we receive them.

4. The churches take liberty (as lawfully they may) to receive or reject at their discretion; yea particular towns make orders to the like effect; why then should the common weale be denied the like liberty, and the whole more restrained than any part?

5. If it be sin in us to deny some men place etc. amongst us, then it is because of some right they have to this place etc. for to deny a man that which he hath no right unto, is neither sin nor injury.

6. If strangers have right to our houses or lands etc., then it is either of justice or of mercy; if of justice let them plead it, and we shall know what to answer: but if it be only in way of mercy, or by the rule of hospitality etc., then I answer 1st a man is not a fit object of mercy except he be in misery. 2d. We are not bound to exercise mercy to others to the ruin of ourselves. 3d. There are few that stand in need of mercy at their first coming hither. As for hospitality, that rule doth not bind further than for some present occasion, not for continual residence.

7. A family is a little common wealth, and a common wealth is a great family. Now as a family is not bound to entertain all comers, no not every good man (otherwise than by way of hospitality) no more is a common wealth.

8. It is a general received rule, turpius ejicitur quam non admittitur hospes, it is worse to receive a man whom we must cast out again, than to deny him admittance.

9. The rule of the Apostle, John 2. 10. [2 John 1:10] is, that such as come and bring not the true doctrine with them should not be received to house, and by the same reason not into the common weale.

10. Seeing it must be granted that there may come such persons (suppose Jesuits etc.) which by consent of all ought to be rejected, it will follow that by this law (being only for notice to be taken of all that come to us, without which we cannot avoid such as indeed are to be kept out) is no other but just and needful, and if any should be rejected that ought to be received, that is not to be imputed to the law, but to those who are betrusted with the execution of it. And herein is to be considered, what the intent of the law is, and by consequence, by what rule they are to walk, who are betrusted with the keeping of it. The intent of the law is to preserve the welfare of the body: and for this end to have none received into any fellowship with it who are likely to disturb the same, and this intent (I am sure) is lawful and good. Now then, if such to whom the keeping of this law is committed, be persuaded in their judgments that such a man is likely to disturb and hinder the public weale, but some others who are not in the same trust, judge otherwise, yet they are to follow their own judgments, rather than the judgments of others who are not alike interested: As in trial of an offender by jury; the twelve men are satisfied in their consciences, upon the evidence given, that the party deserves death: but there are 20 or 40 standers by, who conceive otherwise, yet is the jury bound to condemn him according to their own consciences, and not to acquit him upon the different opinion of other men, except their reasons can convince them of the error of their consciences, and this is according to the rule of the Apostle. Rom. 14. 5. Let every man be fully persuaded in his own mind.

If it be objected, that some profane persons are received and others who are religious are rejected, I answer 1st, It is not known that any such thing has as yet fallen out. 2. Such a practice may be justifiable as the case may be, for younger persons (even profane ones) may be of less danger to the common weale (and to the churches also) than some older persons, though professors of religion: for our Saviour Christ when he conversed with publicans etc. sayeth that such were nearer the Kingdom of heaven than the religious pharisees, and one that is of large parts and confirmed in some erroneous way, is likely to do more harm to church and common weale, and is of less hope to be reclaimed, than 10 profane persons, who have not yet become hardened, in the contempt of the means of grace.

Lastly, Whereas it is objected that by this law, we reject good Christians and so consequently Christ himself: I answer 1st. It is not known that any Christian man hath been rejected. 2. a man that is a true christian, may be denied residence among us, in some cases, without rejecting Christ, as admit a true Christian should come over, and should maintain community of goods, or that magistrates ought not to punish the breakers of the first table, or the members of churches for criminal offences: or that no man were bound to be subject to those laws or magistrates to which they should not give an explicit consent, etc. I hope no man will say, that not to receive such an one were to reject Christ; for such opinions (though being maintained in simple ignorance, they might stand with a state of grace yet) they may be so dangerous to the public weale in many respects, as it would be our sin and unfaithfulness to receive such among us, except it were for trial of their reformation. I would demand then in the case in question (for it is bootlesse curiosity to refrain openness in things public) whereas it is said that this law was made of purpose to keep away such as are of Mr. Wheelwright his judgment (admit it were so which yet I cannot confess) where is the evil of it? If we conceive and find by sad experience that his opinions are such, as by his own profession cannot stand with external peace, may we not provide for our peace, by keeping of such as would strengthen him and infect others with such dangerous tenets? and if we find his opinions such as will cause divisions, and make people look at their magistrates, ministers and brethren as enemies to Christ and Antichrists etc., were it not sin and unfaithfulness in us, to receive more of those opinions, which we already find the evil fruit of: Nay, why do not those who now complain join with us in keeping out of such, as well as formerly they did in expelling Mr. [Roger] Williams for the like, though less dangerous? Where this change of their judgments should arise I leave them to themselves to examine, and I earnestly entreat them so to do, and for this law let the equally minded judge, what evil they find in it, or in the practice of those who are betrusted with the execution of it.[41]

For Further Study

For a history of colonial immigration policies, see Colonial Immigration Laws: A Study of the Regulation of Immigration by the English Colonies in America by Emberson Edward Proper

For a detailed study of Puritan and Pilgrim immigration laws, see Warning Out in New England by Josiah Henry Benton

Notes

______________________________________________

[1] Emberson Edward Proper, Colonial Immigration Laws: A Study of the Regulation of Immigration by the English Colonies in America (NY: Columbia University, 1900), 22.

[2] William Brigham, The Compact with the Charter and Laws of the Colony of New Plymouth: Together with the Charter of the Council at Plymouth, and an Appendix, Containing the Articles of Confederation of the United Colonies of New England, and Other Valuable Documents (Boston, MA: Dutton and Wentworth, Printers to the State, 1836), 314. We have modernized the language.

[23] Massachusetts General Court, The Charters and General Laws of the Colony and Province of Massachusetts Bay: Carefully Collected from the Publick Records and Ancient Printed Books. To Which is Added an Appendix, Tending to Explain the Spirit, Progress and History of the Jurisprudence of the State; Especially in a Moral and Political View. (Boston, MA: T. B. Wait and Co., 1814), 129. We have modernized the language.

[24] Acts and Resolves, i, 423. Cited in Proper, Colonial Immigration Laws, 27.

[25] Hutchinson Papers: Mass. Historical Coll., 3d series, i, 108. Cited in Proper, Colonial Immigration Laws, 27.

Photo credit:

______________________________________________

[1] Emberson Edward Proper, Colonial Immigration Laws: A Study of the Regulation of Immigration by the English Colonies in America (NY: Columbia University, 1900), 22.

[2] William Brigham, The Compact with the Charter and Laws of the Colony of New Plymouth: Together with the Charter of the Council at Plymouth, and an Appendix, Containing the Articles of Confederation of the United Colonies of New England, and Other Valuable Documents (Boston, MA: Dutton and Wentworth, Printers to the State, 1836), 314. We have modernized the language.

[3] John Winthrop, "A Reply in Further Defense of an Order of Court Made in May, 1637," in Winthrop Papers: Volume III: 1631-1637 (Boston, MA: The Massachusetts Historical Society, 1943), 467. We have modernized the language.

[4] Josiah Henry Benton, Warning Out In New England (Boston: W. B. Clarke Company, 1911), 53. In all citations from this work, we have modernized the text.

[5] Compact, Charter and Laws of Colony of New Plymouth, 57, 119. Cited in Ibid., 53, 54.

[6] National Conference on Social Welfare, The Social Welfare Forum: Official Proceedings of The Annual Forum (Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 1922), 458.

[7] John Waddington, Congregational History, 1567-1700, in Relation to Contemporaneous Events, and the Conflict for Freedom, Purity, and Independence (London: Longmans, Greens, and Co., 1880), 319.

[8] William Bradford, "Letter from William Bradford to John Winthrop, 11 April 1638," cited in MHS Collections Online. Retrieved August 11, 2014 from http://www.masshist.org/database/viewer.php?item_id=1708&img_step=1&mode=transcript#page1. We have modernized the language.

[9] Cited in Waddington, Congregational History, 319, 320.

[10] Cited in Ibid., 320.

[11] Caleb Johnson, ed., William Bradford: Of Plymouth Plantation: Along with the full text of the Pilgrims' journals for their first year at Plymouth. (Xlibris Corporation, 2006), 517.

[12] Ibid.

[13] "Reviews: The Pilgrim Republic," in Book News: A Monthly Survey of General Literature: Volume VI: September 1887 to August 1888 (Philadelphia, PA: John Wanamaker, 1888), 498.

[14] Johnson, William Bradford: Of Plymouth Plantation, 393, 394.

[13] "Reviews: The Pilgrim Republic," in Book News: A Monthly Survey of General Literature: Volume VI: September 1887 to August 1888 (Philadelphia, PA: John Wanamaker, 1888), 498.

[14] Johnson, William Bradford: Of Plymouth Plantation, 393, 394.

[15] "The Massachusetts Body of Liberties," history.hanover.edu (1641). Retrieved August 13, 2014 from http://history.hanover.edu/texts/masslib.html. From the webpage: This digital version of a leaflet in Old South Leaflets is part of the Hanover Historical Texts Project. It was scanned by Monica Banas in August, 1996, and it was last modified March 8, 2012. See Old South Leaflets (Boston: Directors of the Old South Work, n.d. [c. 1900]), 7: 261-280.

[16] John Beardsley, Liberties of New Englishmen (Clinton, CT: The Winthrop Society, 1995-2012). Retrieved August 14, 2014 from http://www.winthropsociety.com/liberties.php.

[17] "The Massachusetts Body of Liberties," history.hanover.edu. We have modernized the language.

[18] The Book of the General Lawes and Libertyes Concerning the Inhabitants of the Massachusets (1648; facsimile edition, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1929). Retrieved August 13, 2014 from http://faculty.cua.edu/pennington/Law508/MassachusettsLaws.htm. We have modernized the language.

[19] Proper, Colonial Immigration Laws, 25.

[20] Jack P. Greene, ed., Settlements to Society, 1607-1763: A Documentary History of Colonial America (New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 1975), 174, f.n.

[21] Cited in Ibid., 176. We have modernized the language.

[22] Proper, Colonial Immigration Laws, 25, 26.[20] Jack P. Greene, ed., Settlements to Society, 1607-1763: A Documentary History of Colonial America (New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 1975), 174, f.n.

[21] Cited in Ibid., 176. We have modernized the language.

[23] Massachusetts General Court, The Charters and General Laws of the Colony and Province of Massachusetts Bay: Carefully Collected from the Publick Records and Ancient Printed Books. To Which is Added an Appendix, Tending to Explain the Spirit, Progress and History of the Jurisprudence of the State; Especially in a Moral and Political View. (Boston, MA: T. B. Wait and Co., 1814), 129. We have modernized the language.

[24] Acts and Resolves, i, 423. Cited in Proper, Colonial Immigration Laws, 27.

[25] Hutchinson Papers: Mass. Historical Coll., 3d series, i, 108. Cited in Proper, Colonial Immigration Laws, 27.

[27] William Brigham, The Compact with the Charter and Laws of the Colony of New Plymouth: Together with the Charter of the Council at Plymouth, and an Appendix, Containing the Articles of Confederation of the United Colonies of New England, and Other Valuable Documents (Boston, MA: Dutton and Wentworth, Printers to the State, 1836), 314, 315. We have modernized the language.

[28] Benton, Warning Out In New England, 50.

[29] Brigham, The Compact with the Charter and Laws of the Colony of New Plymouth, 319. We have modernized the language.

[30] Boston Town Records, 1634-1660, 152. Cited in Benton, Warning Out In New England, 25, 26.

[31] Benton, Warning Out In New England, 26. Citation from Town Records of Woburn, Vol. I, 13.

[32] Benton, Warning Out In New England, 33. Citation from Early Records of Lancaster, 28.

[33] Benton, Warning Out In New England, 34.

[34] Ibid., 36.

[35] Records of Massachusetts Bay, 1650, 22 June (20), 23, 24. Cited in Benton, Warning Out In New England, 47.

[36] Benton, Warning Out In New England, 47, 48.

[32] Benton, Warning Out In New England, 33. Citation from Early Records of Lancaster, 28.

[33] Benton, Warning Out In New England, 34.

[34] Ibid., 36.

[35] Records of Massachusetts Bay, 1650, 22 June (20), 23, 24. Cited in Benton, Warning Out In New England, 47.

[36] Benton, Warning Out In New England, 47, 48.

[37] Michael P. Winship, Making Heretics: Militant Protestantism and Free Grace in Massachusetts, 1636-1641 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2002), 136, 137.

[38] Thomas Shepard, "The Parable of the Ten Virgins Unfolded: Section VI," in The Works of Thomas Shepard: First Pastor of the First Church, Cambridge, Mass., with a Memoir of His Life and Character: Volume II (Boston: Doctrinal Tract and Book Society, 1853), 259, 260.

[39] Winship, Making Heretics, 137.

[40] John Winthrop, Winthrop Papers: Volume III: 1631-1637 (Boston, MA: The Massachusetts Historical Society, 1943), 422, f.n.

[41] Ibid., 422-426. We have modernized the language.

A statue of William Bradford in Plymouth, MA

© jeffesp0 / Flickr (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) (license)

Retrieved August 22, 2014 from https://www.flickr.com/photos/jeffesposito/4450628904.

we have cropped the original version

2 comments:

Very interesting material.

The usual storyline about colonial New England is this : the Puritans founded it, but all their children were rebellious so a compromise was made with the Half-Way Covenant of 1662, and then the Great Awakening saved the colonies from ungodliness.

I has always been suspicious if this account, and my hypothesis was that it was maybe more ungodly immigrants than ungodly children that were the real cause behind the Half-Way Covenant.

This article provides multiple primary sources that clearly confirm my hypothesis. So we must not be deceived by fatalism : « even if we make children they will likely become non-Christians ». The history of the Afrikaner people, for example, is proof that genuine Christian faith can be passed on for many generations.

Scolaris, an excellent book for exploring Puritan history and its ups and downs is "The Light and the Glory" by Marshall and Manuel. The Puritans were regularly challenged with setbacks, including King Philip's War, which was considered as a time of God's chastisement.

Post a Comment